We are deluged by horrific stories of the deaths and abuse at residential schools.

We wonder: Why didn’t anyone do anything back then?

A few did, but it takes courage to stand against the crowd.

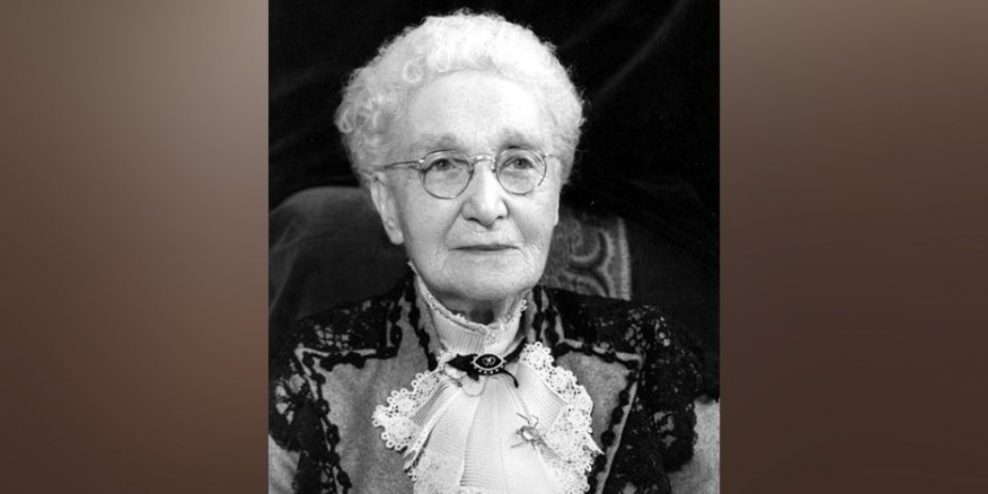

Alice Ravenhill, who died almost seventy years ago, was one of those people.

During the painful era in our history when our governments did eradicate to completely annihilate First Nations’ culture and peoples, Alice fought against their actions.

While she was far from a perfect heroine, she was one of the first to look past the racist messaging she was being fed.

She chose empathy and learning and the actions she took helped change the path of Canadian history.

A proper English “high-society” woman, Alice moved to Shawnigan Lake in 1910.

She was ahead of her time in many ways. She had a university degree and was working and writing books at a time when this was rare for women.

But people are complicated.

“Heroes are more than just stories, they’re people. And people are complicated; people are strange. Nobody is a hero through and through…”

Joel Cornah

Alice devoted much of her life in Canada to helping others, yet before she emigrated from England, she was a huge proponent of Eugenics, the theory of “racial improvement” and “planned breeding.”

While popular during the early 20th century, Eugenics was discredited as unscientific and racially-biased after the Nazis used it to justify their treatment of Jews, disabled people, and other minority groups.

When Alice came to Canada, she changed.

About 10 years after moving–for reasons we may never know–Alice was moved to start learning about First Nations Cultures.

She went into communities to try and better understand cultural differences.

What she learned in them, would change the course of the rest of her life, and many others.

What was at first likely mere curiosity became new respect for Indigenous peoples that pushed Alice to switch her beliefs.

As a woman in her sixties, Alice suddenly became a fierce advocate for Indigenous peoples, particularly their art and culture.

These were, at the time, very unpopular opinions.

Alice’s transformation began by simply acknowledging the reality of what was being done to Indigenous communities.

Ravenhill realized that, in residential schools: “the children are confronted with unknown subjects in an unknown language – diverse from their own picturesque

forms of expression; a process described by Sir George Maxwell in 1942 out of his wide experience as ‘crippling and destroying a people’s soul; fatal to self-respect and inducing in the individual contempt for his own race.’”

Ooof.

While this may seem an obvious observation now, at the time, it was a fact few were courageous enough to say out loud.

Alice decided it was time people did.

To combat the destruction of culture Alice saw happening around her, she started documenting indigenous art.

“To bring to the notice of the public, the innate merits and deep-rooted artistic talents of the Indian people by means of Exhibitions of their Arts and Crafts, Folklore, Music, Drama and Dance,” she said.

Ravenhill acted as a one-woman unpaid Indigenous Studies Department in the 1930s and 1940s, writing three books: Native Tribes of British Columbia (1938), A Cornerstone of Canadian Culture Title: An Outline of The Arts and Crafts of the Indian Tribes of British Columbia (1944), and Folklore of the Far West with Some Clues to Characteristics and Customs (1953).

Was she the best person to write and teach on these topics?

DEFINITELY NOT.

But at the time, she was listened to in a way that Indigenous people weren’t. So she spoke to the best of her ability – using her voice to amplify others.

In 1940, she co-founded the Society for the Furtherance of Indian Arts and Crafts in British Columbia, the society fostered the abilities of artists like Anthony Walsh of Inkameep and Noel Stewart of Lytton — who in turn championed young Native artists like Francis Jim Baptiste (Sis-hu-lk) and George Clutesi of Alberni.

The Society’s main goal was to to promote the welfare, creative talent, and social and economic status of Indigenous peoples.

“Assisting their economic position through some form of revival of their latent gifts, of arousing more interest in the cultural background we owe to them,” she said.

While gains in those areas were slim, one thing it did was change the one-dimensional perception of First Nations.

“To set a Salish man to carve after the method of the Haida or Tsimshian or a Nootkay woman to coil, and imbricate a Chilcotin basket, would be worse than [a] waste of time,” Alice would say.

She also did her best to reintroduce residential children to Indigenous art. Essentially, starting a one woman battle with government residential school facilitators through a flurry of letters and drop ins.

Alice was mainly refused. But in at least in one case, it happened. Alice spoke of the experience with wonder.

“These children eagerly responded to the daily opportunities for self-expression. They acted out old tribal legends, making clever bird or animal masks to complete the realism of their presentations, and they thus stimulated a revival among their grandparents of well nigh forgotten tribal songs, soon memorized by the children, who then translated them into dance with a grace which has to be seen to be believed.”

It was a small win.

Most of Ravenhill’s work could be described this way. The impacts she made were often smaller than hoped, and took huge efforts to make happen.

She made countless mistakes (most of her work would now be considered cultural appropriation.)

But, above all else. Alice tried.

Today, we often discredit seniors by saying they are “set in their ways.” We joke about “old dogs” and “learning new tricks.”

But Alice’s life proves that people can change their minds–and more importantly, drastically change their actions–even in old age.

Alice stood up to a system that didn’t want her to. She empathized and listened to those who were ignored. She did her best to do what was right – no matter what others thought, or how impossible it seemed or even what she had previously believed.

All this after living the entire first half of her adult life preaching that some races were simply better than others. Yikes.

While we may never know why, Alice’s reversal and doggedness make us hopeful.

Alice never gave up. She persisted in her good works even after she was completely bedridden.

Alice passed away in 1954. To most, she was forgotten.

An unpopular woman then, and likely still an unpopular woman now.

But we think Alice should be remembered–not for her white saviour complex, or allyship, depending on how you view it.

But, for her ability to change.

Our opinions and ideas are not set in stone. They are changed through fostering empathy and understanding.

People can learn, change, and grow–even as seniors. People with views that might make you want to start throwing punches, can reverse course.

The point of exploring history is to learn from it.

There’s a lot of hate and misinformation in our world right now. So the next time you encounter it, remember Alice.

If she could change, so can you… and your bitter rivals.