Indigenous people have lived on VanIsle for thousands of years. Folks from the Lekwungen in the south to the ‘Namgis in the north have lived countless lives on this land.

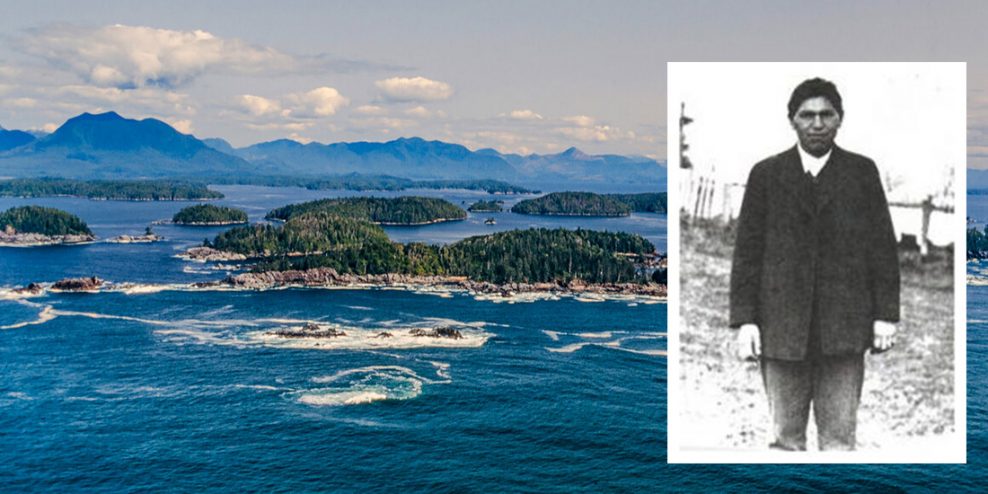

Today, we’re remembering the life of Alec Thomas.

Alec was a Tseshaht man born in Port Alberni over a century ago. Born in 1894, like thousands of young Indigenous children of the time, Alec was forced to attend residential school.

He came out of that system fully bilingual. This was rare, as most children lost their ability to speak their traditional language after being forced to speak only English.

At 18 years old, he was one of only two bilingual speakers in his town. And he used his ability to defend and preserve his culture, language, and traditions in every way he could for the rest of his life.

Alec became an interpreter between his people and the fast encroaching colonizer society.

He was a tireless community leader for the Tseshaht. Given how few people in the older generations spoke English at the time, they were often unaware of the kinds of foreign laws being imposed upon them. People we’re frequently arrested without even knowing why. (Hint: they were arrested because of racism and systemic cultural oppression.)

Alec was there to advocate when folks were jailed or had to appear in court.

When the federal government tried to take away the Tseshaht right to fish, the community raised money to send Alec to Ottawa to fight for their rights. He stayed in Ottawa until he received the guarantee of a drag seine fishery on the Somass River, a fishery that’s still in use today.

When the construction of the railroad threatened Tseshaht houses along the river, Alec was there to fight for Tseshaht lands and homes.

Alec worked hard to maintain what today we call Indigenous Rights and Title, the same issues Tseshaht and other First Nations are fighting for today.

He was also a holder of songs for the Tseshaht people and kept many stories alive that may have otherwise been lost.

But all of these activities were just how he spent his free time.

He started working in 1910, at just 16 years old, for a Jewish American anthropologist named Edward Sapir. They worked together for over 20 years. During this time, Alec ran interviews with elder historians in the community.

He eventually travelled to Chicago in 1933 to finalize the oral history for publication, which helped further spread knowledge of his people’s history and culture.

Besides this, he also worked as a fisher and had a trap line that ran 14 miles from the Somass River up to Sproat Lake. This helped to feed his wife Eva and his son Bob, as well as the rest of the community.

When potlatches (one of the Tseshaht and many other First Nations’ most significant cultural ceremonies) were criminalized, Alec worked with Sapir to document as many as possible. He wanted to ensure the practice would not be forgotten.

He eventually hosted one of the last potlatches.

In a time when it was not only difficult but often illegal to practice Indigenous customs, Alec persevered. The practices, culture, and people he helped keep alive are still celebrated today.

For that, we honour him.

We honour Alec Thomas and the countless people who fight tirelessly for a better life and future.

Going forward, may we be them.